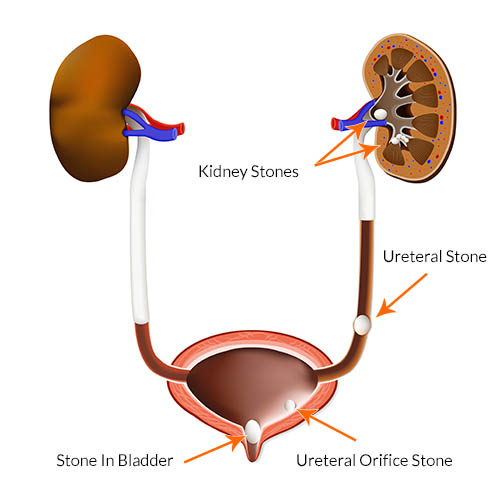

Kidney Stones

Another very common problem seen in an Urologist’s office, particularly here in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern United States (sometimes referred to as the “stone belt”) is kidney stones. Unlike years past where urinary stones were often managed with open surgery, today stones that do not pass on their own are nearly always treated in a minimally invasive fashion. The most common factor contributing to kidney stone formation is inadequate water intake, which many/most of us are guilty of. However, some patients will have specific metabolic abnormalities or hormonal abnormalities that predispose them to stone formation. If such an abnormality is suspected, special test will be performed and chronic medication may be prescribed. For most cases however, the key to stone prevention is simply increasing water intake.

If a stone can be seen on a plain x-ray, it is a calcium stone. These stones cannot be dissolved, and must either pass or be treated. On the contrary, uric acid stones comprise perhaps 10% of all stones, which if not coated with calcium, can be dissolved by raising the pH of the urine.

The vast majority of stones are calcium stones, either calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate. If a stone can be seen on a plain x-ray, it is a calcium stone. These stones cannot be dissolved, and must either pass or be treated. On the contrary, uric acid stones comprise perhaps 10% of all stones. These stones can form spontaneously, but can also be a result of high blood uric acid levels, a condition that can also cause a disease called gout. What is unique about uric acid stones is that they can, if not coated with calcium, be dissolved by raising the pH of the urine. One of the first things an Urologist will want to determine is whether a uric acid stone is suspected or not when a stone is present as this may affect how that stone will be managed.

Stones are discovered in one of three ways. A patient may undergo a radiologic exam for an unrelated reason when a stone is found incidentally. A stone can be found as a result of a workup of hematuria, or blood in the urine, or a stone can be found when it decides to pass. Stone passage presents itself in many ways. Although the old adage is that stone passage is very painful, often likened to childbirth, this is not always true. Rather, many stones are very small and hardly noticed other than perhaps having what is felt to be an upset stomach or irritative urinary symptoms as the stone approaches the bladder. In some patients there is no pain at all, with perhaps the only sign that a stone is passing being the presence of blood in the urine. It is important to understand that pain occurs with a stone only when it is obstructing the flow of urine from the kidney to the bladder via a tube called the ureter. If a stone is small enough, it can slowly pass down the ureter without causing much obstruction and thus not much pain. It is for this reason that stones in the kidney itself are largely asymptomatic, a fact that surprises most patients.

When a stone is uncovered, the most important detail that must be known to advise the patient as to what to do is the size of the stone. Very small stones (1-3 mm) in the ureter are left to pass on their own if at all possible. The patient will be asked to urinate through a strainer until the stone passes. All too often a patient will not be compliant with the strainer, or will assume that lack of pain equals lack of stone. This is not a safe assumption. Dr. Engel will insist that either a stone is collected if previously shown to be passing in the ureter or a repeat radiologic study will have to be gotten to prove that the stone has passed. In some rare cases, even a very small stone can stay in the ureter asymptomatically and slowly obstruct and damage the kidney, sometimes beyond repair.

However, larger stones that are 5mm or larger are more likely to become lodged in the ureter and not pass on their own. This is when a patient may be given a choice of waiting longer to see if it will pass or choosing to have the stone treated.

However, larger stones that are 5mm or larger are more likely to become lodged in the ureter and not pass on their own. This is when a patient may be given a choice of waiting longer to see if it will pass or choosing to have the stone treated. A kidney is remarkably resilient, and can withstand obstruction for a period of a month or at times even longer, so it is the patient’s schedule and discomfort or imposition on their life that usually dictates the timing of management. If action is chosen, the two most common procedures offered are ESWL, or extra-corporeal shock wave lithotripsy, or ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy. If stones are very large, a far less commonly utilized and more invasive procedure called a percutaneous nephrolithotomy will be recommended.

ESWL was popularized in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. Before its introduction, open surgery had to be used. ESWL is a procedure whereby the patient is anesthetized and a machine called a lithotripter is used to fire sound waves at the stone. The original ESWL machines involved placing the anesthesized patient into a water bath as a means of transmitting the sound waves to the patient. Now, several generations later, these machines are portable and much smaller and simpler. ESWL can be used for stones lodged in the ureter, but is more often used for stones in the kidney. ESWL is the most minimally invasive procedure for kidney stones, but its success rates at producing a stone free kidney likely top out at 90% or so. Sometimes a stone will be treated with more than one lithotripsy or in combination with ureteroscopy.

Ureteroscopy was introduced, and became a very common treatment in the early 2000’s. What truly allowed ureterscopy to develop was the emergence of the use of lasers in Urology, and the progress made in fiber-optic technology. Now, ureteroscopes are very thin, are rigid or flexible, thus allowing nearly all stones to be treated this way. Here, instead of an x-ray guiding sound waves as in ESWL, the Urologist uses a scope to reach the stone directly, sees the stone on a video monitor, and uses a laser beam as the energy source to destroy the stone under direct vision. Ureteroscopy will generally require a temporary ureteral stent, which some patients would prefer to avoid but with some exceptions are generally well tolerated. Ureteroscopy is the most common way to treat ureteral stones but can treat kidney stones as well. Success rates with ureteroscopy are slightly higher than with ESWL, but it is a somewhat more invasive procedure that will require stent placement and stent removal at a later date. Both ESWL and ureteroscopy are typically done in an outpatient surgical setting, and it must be understood that in both cases small stone fragments will still need to be passed. The stones do not simply disappear.

As stated above, a percutaneous nephrolithotomy is a much more rare procedure. In the hands of Dr. Engel, this will be offered in the setting of a very large stone, perhaps 3cm or greater. Here, a needle is placed through the back directly into the kidney. This tract is used to place a tube called a nephrostomy tube, and this access will be used in the operating room to allow the Urologist direct access into the kidney with a much larger scope. A nephrolithotomy carries with it more risk such as bleeding, and will require an overnight hospital stay, but at times is the only viable option for some stones.

All patients must know that perhaps the most serious complication after a stone procedure is infection.

All patients must know that perhaps the most serious complication after a stone procedure is infection. Fevers after a procedure could signal infection behind an obstruction, an emergency situation that could rapidly progress to a condition called sepsis which can be life threatening. Fevers or feeling very sick after a stone procedure is always an emergency, so please dial 911 or go to your nearest or favorite emergency room and ensure that Dr. Engel or Dr. Tobon are contacted to take part in your care. As a reminder, USW physicians have privileges at Reston Hospital Center, Holy Cross Hospital Silver Spring, and Holy Cross Hospital Germantown.

If you have been diagnosed with a kidney or ureteral stone, we would be happy to review your films/cd with you during a consultation in our office and make recommendations.